Dieter Ravyts

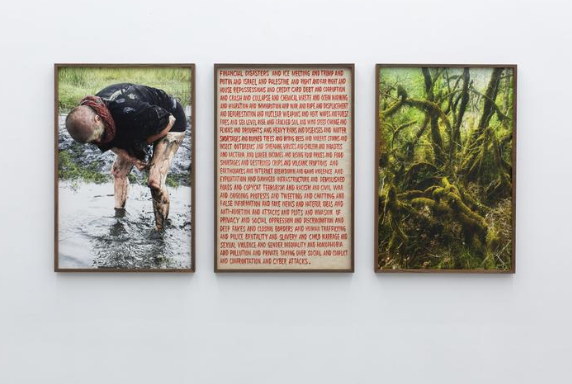

“The Short End of the Stick”

April 25 - May 18, 2025

Dieter Ravyts (Belgium, 1988) work can be seen as a chain reaction, an ongoing story where one idea flows out of the other. Up until now, the main focus of his work has been manmade constructions (such as machines) and manmade abstractions (like written language). He also has a fascination with modernism and its utopias.

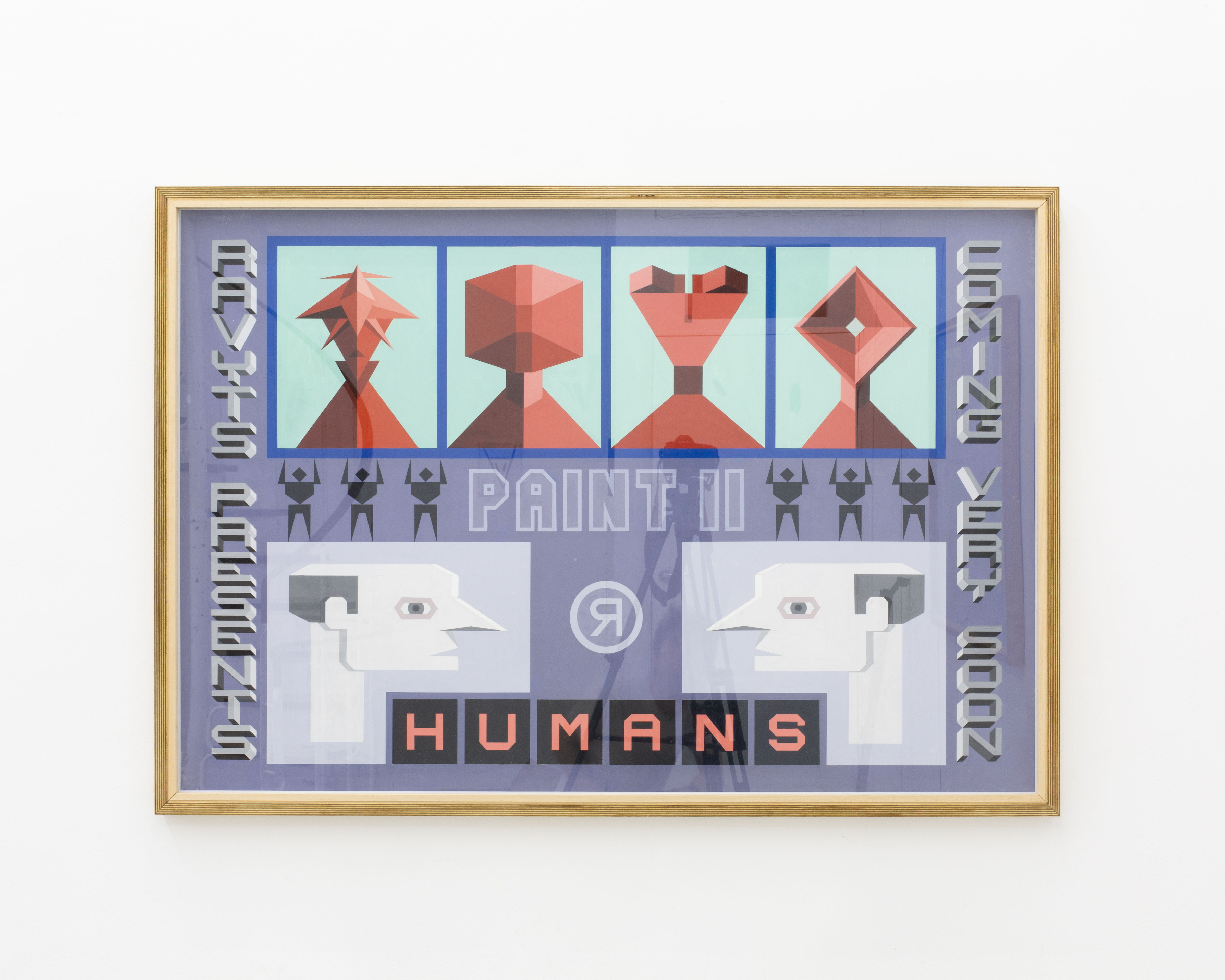

His Affiche-Painting series was a first exploration of these ideas. This series consists of large, painstakingly painted posters that announce works yet to come.

The artist began making these posters as a way to delay making the ‘main work’ out of fear of failure. Initially, they served as a means of postponement, but over time, they evolved into a body of work in their own right. However, the works they announce have yet to be made.

In the margins of the Affiche series, a new series emerged: Lettrism. In this series, the artist repurposes the letters from his posters to create figures and portraits and by doing so assigning new meaning to the letters. Lettrism also functions as a transitional phase between the posters and the figurative works the artist intends to create—works that, of course, have already been announced but have yet to come into existence.

The Short End of the Stick

My name is telling of the kind of person I was destined to become. A particular kind of ill-starred thread was braided into my being from the beginning. One might assume it’s rooted in some Scottish or Irish heritage, but Mother insists it’s a reference to Shakespeare’s Desdemona. She told me the story of my naming even before I was old enough to grasp its significance. Since then, I’ve asked her to repeat it often.

I held you in my arms in the visitors lounge of the town hall, waiting to get you sorted out. You were cooing like a wood pigeon catching the morning sun. Only a few days old. I was flipping left-handedly through brochures about parenthood I couldn’t understand, when I saw a poster pinned to the notice board. I was told it was from the regional theater. The name ‘Desdemona’ stood out, second in line, long and bold. I thought it looked beautiful, important, slightly Gothic. I considered those excellent qualities for a person, so I copied the shapes in my sketchbook to present to the town hall clerk. Afterwards there was some silly discussion about it being a girl’s name. So, we settled for Desmond.

One might be surprised to learn that Mother is illiterate. She chose names for me and my brothers (Нижинский, 毛澤東, Francis, and Iggy) based on how their lettering looked on posters. Drawn to their shapes, elegance and symmetry, writing became painting. To her, posters were imperative. They were her religion, her politics, her joy. Having lived a largely nomadic life, she’d collected them as one would postcards, stamps or seashells from here, there, and everywhere. The flat where we were raised was plastered with them from floor to ceiling, like a shrine. Especially precious ones were framed and hung on top of the DIY-wallpaper of tattered edges and peeling glue.

You can imagine her delight when I got hired to be an afficheur. I became a professional. A perfectionist. The Factory Manager would call on me when things needed to be posted quickly and neat. I took pride in the recognition, though I privately detested the grime on my hands, the crusted glue, the bitter reek of ink and solvent. Every time I complained, Mother would respond, like a mantra.

When one is born to do the dirty work, one does not concern oneself with its so-called dirtiness, but rather with its wild, wondrous beauty.

At first I looked forward to collecting the prints at the printer’s, sneaking a peek before carefully rolling them up and loading them into my satchel for the night’s route. But over time something changed, the images started to affect me.

The first time it happened, the bundle included promotional material for an Art Deco exhibit, a call to action for unemployment benefits (something about machines behaving like humans, or the other way round—paranoid propaganda), and an ad for A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the National Theatre. After collecting the prints, I cycled over the cobbled streets as the sun sank below the city’s slumped shoulders, leaving behind a sky ablaze with colour until velvety, blackish-blue spread overhead. Under the dim glow of the street lanterns, I set up the ladder and got to work. Meticulously, I prepared the wall, wiping it clean with a cloth. Spreading on the lumpy paste, catching stray blobs as they slid down the surface, scooping them up with the brush and smoothing them out—up, right, down, left, up again, finishing with two diagonal strokes that dissected the space where the poster would go. I paused to study the print. Leaning back a touch too far, I lost my balance. My weight teetered back and forth for seconds that felt like minutes. I closed my eyes in anticipation.

When I came to, I was lying on my side, cushioned by forest floor. Two dogs, an ass, and a trio of snakes stared at me from their respective places on the edge of the clearing, wide-eyed and blinking slowly. A slight migraine wrapped itself around my head like a crown. My limbs tingled, as if announcing some strange arrival—an omen of presence. However the vibrance of the colours warmed my skin. The simple clarity of the lines stunned me. In the distance I noticed a massive grouping of totem-like sculptures, painted bone white, spelling out the letters:

D, E, S, D, E, M, O, N, A

They spun and twisted at a nauseating speed, but only sideways, like hieroglyphs, as if above and below, back and front had become inaccessible directions. Hypnotized by their strange beauty, I realized too late that the ‘O’ had disconnected itself from the sequence. Its centre popped out, then launched toward me.

Blubbering, I vomited up gulps of paint, ink, and glue. Since then, I resurfaced, many times over, into a world of three painful dimensions. The letters and inky faces, dry and still, beamed at me from the wall above. Waking up after a shift began to feel like an ouroboros of agony, as if I was living, or rather trapped in one dimension too many.

I never told Mother about these episodes. After my naming, it took some time for her to learn the true tragedy of the Venetian Desdemona, the ill-fated one. She found, in her own way, some poetry in this information. Not concerned in the slightest that she might have cursed her child with some aptronymic prophecy. She proclaimed, over and over, like a mantra.

The name ‘Desdemona’ stood out, second in line, long and bold. I thought it looked beautiful, important, slightly Gothic.

Text by Febe Lamiroy

Installation Views

Works

Related Artists

☞ Dieter Ravyts